Instagram head Adam Mosseri recently told the BBC that all graphic images of self-harm would soon be removed from the social platform. The decision came after Ian Russell said that seeing suicide-related posts on Instagram “helped kill” his 14 years-old daughter Molly – who committed suicide last year.

So it has taken over a year for Instagram to decide to do anything about these images, which means that more young lives may have been put at risk in the meantime. And moreover Mosseri can’t even confirm when the changes will be made. Asked about the delay he told the BBC that Instagram was trying to balance “the need to act now and the need to act responsibly“.

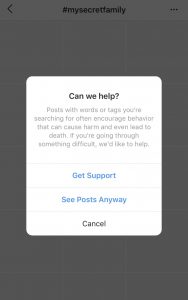

One of the most popular mental health-related hashtags out there is #mysecretfamily. But this secret ‘family’ is one that no one should want to be a part of, as the family members include anorexia, bulimia, anxiety, and insomnia. But instead of naming these conditions for what they are, young boys and girls are encouraged to give them names like Rex (for Anorexia) and Annie (for Anxiety).

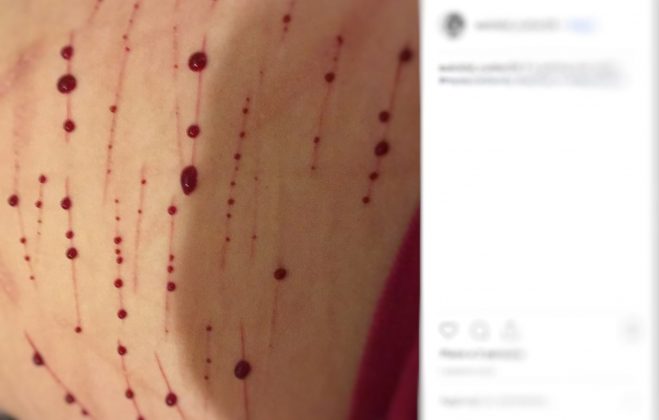

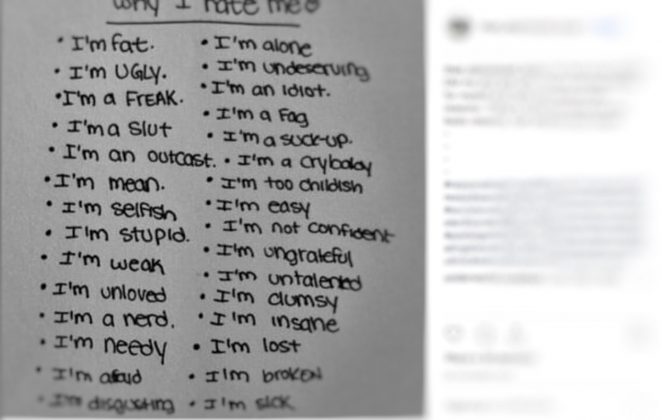

I decided to check out some of these problematic hashtags myself, and quickly felt overwhelmed by the images of bloody wrists and anorexic bodies accompanied by sad quotes and suicide-related videos etc. After spending time online with this content even I felt depressed, and I’m an adult with nothing to feel down about. So how must this material affect impressionable young people with real problems?

Amongst the many communities available on Instagram is one called Respect for Suicide Angel. It’s easy to reach. Just search for #respectforsuicideangel. Vice magazine spoke to a member of the community who described the mindset of its members as follows: “In our eyes, everyone who commits suicide becomes an angel. If your whole life was spent in hell, you belong in heaven. We envy those girls for having the courage to do what we all want to do, but we also respect them for bearing so many years before ending it all.”

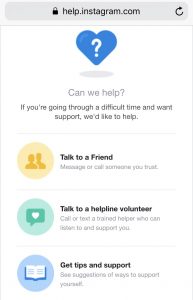

When you come across one of these hashtags on Instagram, the following message pops up: “Can we help?” You can then decide if you want to “get support” or “see posts anyway”.

In my view offering support, particularly to young people who might not know where to get it, is responsible and helpful. But given what is at stake I do not think that asking a young person if they want to continue our not is prevention enough.

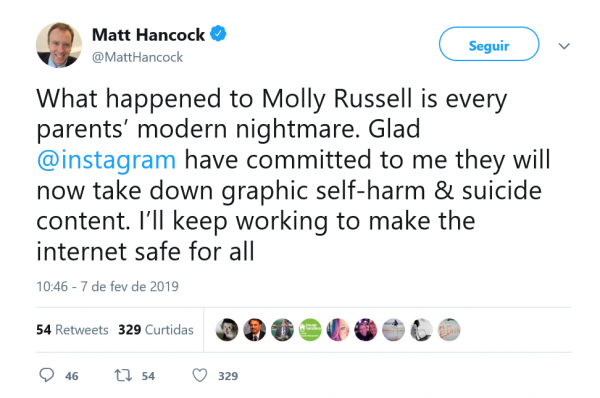

Health Secretary Matt Hancock supports Instagram’s decision to remove graphic images, and refers to what happened to Molly Russell as “every parents’ modern nightmare”. The question is, will the social media giants do enough to help end this nightmare?

Mosseri also told the BBC said that some images of self-harm would still be allowed: “I might have an image of a scar or say, ‘I’m 30 days clean,’ and that’s an important way to tell my story,” he said.

The point he’s making is that it is sometimes helpful for people to share their stories and feel part of a community. But is an anonymous unregulated online community really a community at all? And so is this the right way or the right place for young people to gather around such sensitive issues? Perhaps, instead of helping disturbed children, these sites just disturb them more.