Women challenge the world to include them in STEM

Mike Butler explores the challenges facing women in STEM.

A challenge has been laid down worldwide to increase the number of women working across all fields of science.

Having more women working in science will benefit millions, and yet attempts to make this happen have stalled over the last decade, at least in the UK. Government ministers, a number of them women themselves, have made promises, set up enquiries, and put forward plans, but with limited success.

In 2013 Jo Swinton, who was a Women and Equalities minister under Nicky Morgan at the time, told the Guardian, “Although we know girls out-perform boys at school, this does not always translate into future success in their working lives.”

The current Minister for Women, working under Liz Truss, is Baroness Stedman-Scott. In March she launched a campaign that has helped create a situation in which there are now more women in work than ever before. But STEM is still a male-dominated workplace in the UK.

Women are seriously under-represented in this sector, particularly in engineering and IT. Not only are women missing out on what can be a highly rewarding career, but UK companies are missing out on a huge pool of talent.

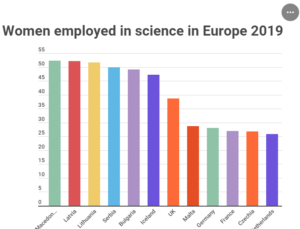

Figures from UNESCO show that the United Kingdom in 2019 was nowhere near the top of European league in this area.

The top five nations in Europe were: North Macedonia (52.3%); Latvia (52.2); Lithuania (51.6); Serbia (50.0); and Bulgaria (49.1). The United Kingdom was 20th at 38.7%. The lowest five were Malta (28.7); Germany (28.0); France (27.0); Czech Republic (26.8) and the Netherlands (25.8).

Extract of data from UNESCO report (UNESCO, Institute For Statistics, June 2019)

The UK has some of the most advanced tech and science-based companies in the world, working in areas such as satellite production, and yet we find ourselves so way down the list.

The most up to date figures available are the reports on-line produced by Women in STEM, which show slight but significant increases across the board. But the same site warns that general uncertainty caused by the pandemic may now lead to a drop, as women are forced to wait for their preferred opportunity and instead take any job that they can in the short term.

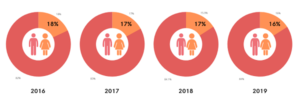

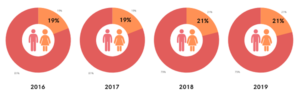

The Women in STEM figures show that female graduates are taking up to at least a third of physical sciences and maths jobs available. But in engineering and IT, the take up by women remains stubbornly low.

Women working in IT

Women working in Engineering

Data taken from the Women in Science and Engineering (WISE) website shows that although the number of jobs available in the areas of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) areas have increased over the past four years, the percentage of women who get them has not.

More funding could help put this right. Increasing the number of women in STEM is just the beginning as far as diversity is concerned. STEM jobs also need more people from the BAME, LGBT+, and disabled communities, as well as more of those who are affected by poverty. More diversity means the research carried out will be more diverse – as will the research outcomes.

This will improve every area of life. For example, the work that Sky at Night presenter Maggie Aderin-Pocock has done on the James Webb telescope has led to developments in optics that have enabled new treatments for those with eyesight disorders.

People who have experienced real poverty bring their insights into their research, and by doing so help promote positive societal change.

If we are to solve some of the world’s most pressing issues, such as food shortages, water poverty and climate change; and win our wars on cancer, HIV, and other diseases; as well as reduce crime, etc. etc., then we need to involve all sections of society.

This means widening the recruitment processes; funding attempts to reduce the achievement gaps; and getting more diverse people to consider careers in the various science disciplines.

It is up to us to pressure politicians to do what is necessary. Then by the mid part of this century, we may be able to start reaping the rewards of this investment.

There are already some good ideas out there, such as the WISE ten steps programme. Increasing the profile of women in STEM will increases interest in STEM subjects and careers generally. This can only be positive, but much more needs to be done.

The gender pay gap and bias in STEM

Maxi Pfeiffer finds evidence of a pay & gender bias in STEM.

Women in STEM enter an industry pervaded by a gender bias. A 2015 research article by Ian Handley Elizabeth Brown, Corinne Moss, and Jessi Smith claims to show that women are disadvantaged in STEM, and this may be down to gender stereotyping.

The study found that men, especially those in academia, judged some authentic research that showed women were disadvantaged in STEM as of lower quality than some fake research that claimed there was no gender bias in STEM. According to the authors this shows that there is an unwillingness amongst men in STEM to accept any evidence that there is gender bias in STEM.

In her book Invisible Women, the author Caroline Criado Perez says, “Numerous studies from around the world have found that female students and academics are significantly less likely than comparable male candidates to receive funding, be granted a meeting with professors, be offered mentoring, or even to get the job”. Also, students tend to treat and perceive female instructors/professors differently than they do male instructors/professors.

A 1968 American Psychological Association study by Philip Goldberg found that students tend to rate research more highly when they think men have done it. “Less effective male professors routinely receive higher student evaluations than more effective female teachers”. If female professors aren’t warm and accessible, they are penalised. But when they are friendly and accessible, they are punished for not being professional.

The 2015 study mentioned above shows that mothers especially face even more barriers in the workspace. They are paid less and are often perceived as less competent. Although parenthood often reinforces upward career trajectories for men, it can become an exit ramp out of intensive careers for women. Mothers face salary penalties even though they contribute the same work and are expected to leave their jobs to care for the family.

The Pew Research Centre has found that in STEM fields, men earn 40% more than women in America. In 2019, earnings for a full-time, year-round worker aged 25 and older was $77,400. But there are significant pay gaps across gender and racial groups. Asian men earned up to $103,300 in 2019; white men earned $90,600; and Hispanic men and black men earned $73,000 and $69,200 respectively.

On the other hand, Asian women earned $88,800; white women $66,200; and black and Hispanic women $57,000. “This significant gap in earnings between women and men in the STEM field leads to significant differences in the ability of women and men to pay off debts incurred as part of their undergraduate and graduate education and to establish a solid financial footing as they move through their peak earning years and into retirement.”

United States salaries 2019 (Research, April 2021)

The role of African “patriarchy”

Khadijat Akande looks at how Africa fares, and finds a similar picture.

“A woman’s place is in the kitchen” or “you should be worried about taking care of your family, not pursuing a career. Leave it to the men!”. These are phrases that the older generation of Africans were used to. Women were subordinate and barely had the opportunity to make decisions themselves. But women have been fighting for their voices, and things have changed drastically since then.

Two African women who have made it in STEM are listed below. Veronica Okello from Kenya is researching green approaches to cleaning heavy metals such as chromium and arsenic. Aster Tsegaye, an HIV/AIDS researcher, is helping to train researchers in Ethiopia. But though women such as this are changing the face of their continent, African women are still under represented in STEM.

Women account for just 30% of sub-Saharan African Researchers, and by not bridging the gender gap, the continent is out of step with global aspirations for gender equality. This means that Africa is missing out on a more gendered approach to global health issues that disproportionately affect women and girls, such as the burden of infectious diseases.

There are many reasons why African women are underrepresented in STEM: lack of funding and empowerment; patriarchy; self-doubt; stereotypical family responsibilities; sexual harassment; and so on.

But according to the research by IAVI in the table below, over 60% of respondents thought that patriarchy was the most significant reason.

| % of respondents who agreed that | 396 | (%) |

| Negative traditional beliefs that women are inferior to men are contributing to girls’/women’s lack of enthusiasm for STEM in secondary and tertiary studies | 289 | (75.3) |

| Majority of girls prefer to study arts subjects and the softer sciences such as biology and geography | 284 | (71.7) |

| Traditional perceptions that “a woman’s place” is not the hard sciences | 287 | (72.5) |

| Hegemonic masculinity influenced by socio-cultural values and beliefs plus organisational gender inequality perceptions among both males and females affect women in pursuing STEM | 287 | (72.5) |

| Sexism and stereotyping of women’s roles | 312 | (78.8) |

| Casting females into supportive roles due to socio-cultural norms | 321 | (81.1) |

| Patriarchy is responsible for the masculine image of STEM | 252 | (63.6) |

| Discrimination for women in accessing decision making positions | 300 | (75.8) |

Figures published by IAVI (April 2020)

IAVI Survey on

Other findings included the following: 61% of the participants needed to prove to themselves that they were as capable as men; and nearly 80% of women deal with obstacles that men don’t.

On recruitment and promotion: 90% of women agreed that they were recruited on merit, but only 56% reported that they were sufficiently rewarded based on their academic and professional qualifications.

On bridging the gap, the report recommended awareness-raising of the importance of STEM education for women; mentorship; and more training: “Giving women more opportunities, giving them a platform to showcase whatever they can… I feel that would help – just giving them equal opportunities”.

We all rely on science, and good science is not the exclusive realm of one sex, social group or faction. When science makes progress, it benefits the whole world. By excluding or degrading the work done by half the world’s population, we are losing out on ideas, discoveries, and progress.

Looking at the WISE website, it is clear that a few simple steps are necessary to make STEM more inclusive, and that this will benefit everybody.

Text: Khadijat Akande Mike Butler, Maxi Pfeiffer

Data Visualisation: Oskar Rabicano