MPs on a cross-party Commons Home Affairs Committee have demanded that Priti Patel’s Home Office should be stripped of responsibility over the Windrush compensation scheme.

This comes after their report revealed that only 750 out of 15,000 victims have received compensation so far, with 23 victims dying before receiving their compensation.

The report accused the Home Office of requiring claimants to go through a “daunting application process” with “unreasonable requests for evidence” which meant that some were rejected because they were unable to provide pay slips for jobs they were refused because the didn’t have a passport.

And the fact that they didn’t have that passport was the fault of the Home Office anyway. This is because most of the Caribbean immigrants who arrived on the Windrush were children travelling on their parents’ passports, and as adults had yet to formalise their residency status.

Light was first shed on this problem in April 2018 at a meeting at the Jamaican High Commission in London at which politicians demanded a solution for a situation in which, because of changes to the immigration system, people who had been living and working in the UK for years were being labelled as illegal immigrants.

This meant that elderly Caribbean immigrants and their children could be denied access to NHS healthcare with some even being charged for access to treatment. There were also examples of people who had worked in their professions for over two decades losing their jobs – and also instances of people being threatened with deportation.

Patrick’s Story

I spoke to one of the victims of what has come to be known as the Windrush scandal: Patrick Wilfred Brown. Patrick, 58, was born in Jamaica but moved to the UK when he was five years old. He first worked on the London underground, constructing the lines in the 80’s, and later became a carpenter.

Then as a result of the scandal, he was suddenly told he did not have British citizenship and was put in a detention centre.

After around seven weeks in detention, Patrick was told he would be deported back to Jamaica on a flight that was scheduled to leave in a little over a week. He was not married and had no children to support his case, but fortunately other family members managed to help him get legal aid which stopped him from being deported.

But even after the deportation had been stopped, he was still detained for a few more weeks while the authorities figured out “what would be the next steps.” The time spent in detention meant that Patrick lost the benefits he had been getting, and so he became homeless.

“The whole experience was traumatizing,” said Patrick, “that’s the only way I can put it. I never thought that me, Patrick, who has been in this country my whole life would be locked away like an animal and treated like an illegal immigrant.”

“My parents bought me here as a child. I became an adult and built a life for myself. I had never felt so low and if I didn’t know God I wouldn’t have made it through.”

Patrick ended up being homeless for around five years, moving between hostels and family members. Then the compensation scheme became available and he worked with solicitors who helped him through the application process and argued his case on his behalf.

More than seven years after he was first detained, Patrick finally received £73,000 in compensation.

“I received my compensation after a long fight,” he said. “The money is like putting a plaster on a wound. The plaster won’t heal the wound; but overtime my body will heal itself. Me too I will heal. I feel like I am starting over, but I will get there.

“Our parents helped rebuild this country. We are not illegal immigrants. We are not all criminal and this should have never been the narrative. The government should learn from this whole thing. Handouts will not fix the broken system. Only they can fix it.”

The way last week’s report put it was this: “No amount of compensation could ever repay the fear, the humiliation and the hurt that was caused both to individuals and to communities affected.”

The Background

The Windrush generation were a strong, ambitious group of over 550,000 Caribbean immigrants who arrived on British shores between 1948 and 1973. These immigrants – who were from Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago and many other islands – came to Britain with the hopes of a better life due to the promise of jobs following World War Two, and the need to rebuild Britain.

The first HMT Empire Windrush ship carrying 1,027 people, arrived in the UK on 22 June 1948.

These immigrants, including my own grandfather, who travelled on the Empire Windrush, came to the UK to work, and not for pleasure. Despite them migrating from their home countries with high hopes for living in Britain, they were not always met with warm welcomes.

This was the 1950s, and my grandfather told me how many of the white population reacted badly to the arrival of so many black workers. Some companies refused them jobs just because of their colour, and racism, both on the streets and at school, was common.

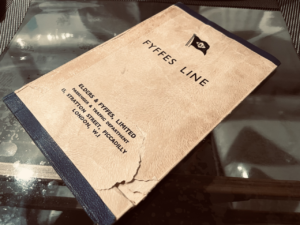

This made it hard for the Windrush generation to make friends with white people, and some of these barriers have not gone away. The picture below shows the boarding pass my grandfather used to travel to the UK with Fyffes lines.

And these official stamps show how long that journey in 1953 took him: over a month.

Anita’s Thoughts

Anita Johnson, 72, lives in Dalson. She arrived from Jamaica on the Windrush after being sent for by her father. He had arrived in 1953 and worked hard until he could afford to buy a property for his family. He then sent over for his wife and children so they could swap hardship back in the Caribbean for a new home, new school, and a new beginning. In the recording below Anita tells us what she thinks about the Windrush scandal.